by Susan Bartlett, Ph.D.

- Benefits of Physical Activity for Individuals with Arthritis

- Physical Activity Recommendations

- The Physician’s Role

- Approaches to Physical Activity

- Exercise Adaptations for People with Arthritis

- Getting Started

- Keeping it Going: Exercise Supervision and Training

- Selected References

- Additional Resources

Benefits of Physical Activity for Individuals with Arthritis

Physiological Benefits

The physiological benefits of exercise are well documented and include reduced risks of: (ref 1)

- coronary artery disease

- serum lipid abnormalities

- hypertension

- diabetes

- osteoporosis

- obesity

- colon cancer

Physical activity is essential to optimizing both physical and mental health and can play a vital role in the management of arthritis. Regular physical activity can keep the muscles around affected joints strong, decrease bone loss and may help control joint swelling and pain. Regular activity replenishes lubrication to the cartilage of the joint and reduces stiffness and pain. Exercise also helps to enhance energy and stamina by decreasing fatigue and improving sleep.(ref 2) Exercise can enhance weight loss and promote long-term weight management in those with arthritis who are overweight.

Exercise may offer additional benefits to improving or modifying arthritis. As Dr. Steven Blair, Exercise Epidemiologist and Director of Epidemiology at the Cooper Institute for Aerobics Research in Dallas TX notes “Skeletal muscle is the largest organ in the body and is intricately tied with protein turnover and synthesis and many other metabolic and biochemical functions. Activating skeletal muscle has many important health benefits we are only beginning to understand.”

Psychological Benefits

The psychological benefits of exercise are equally compelling.(ref 1)

In the short-term (i.e., immediately after exercising) exercise:

- decreases anxiety

- improves mood and well being

- promotes a state of relaxation

A growing body of empirical research also suggests that exercise has long-term effects on well being as well. Improvements in mood and well being have been reported by regular exercisers in both clinical and non-clinical populations and with most types of exercise. Baseline levels of anxiety are lower in individuals who exercise regularly as compared with sedentary adults. Thus, exercise appears to be a potent stress reducer as well. In at least one major clinical trial sponsored by the National Institutes of Health, exercise and group counseling is being tested by clinicians (who are qualified to assess and monitor the disorder) as a primary treatment for mild depression. Because depression is a concern for individuals with arthritis, physical activity is an important psychological adjunct to treatment. Though more research is warranted to confirm these findings, preliminary studies suggest that moderate-intensity lifestyle exercise, such as walking, is as effective as traditional vigorous aerobic exercise in improving mood.

Physical Activity Recommendations

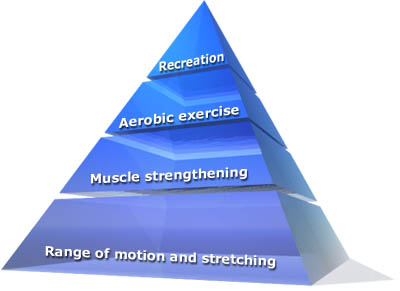

The goals of an exercise program for individuals with arthritis are to: 1) preserve or restore range of motion and flexibility around affected joints, 2) increase muscle strength and endurance, and 3) increase aerobic conditioning to improve mood and decrease health risks associated with a sedentary lifestyle.(ref 3) The exercise program can be organized around the Exercise Pyramid for Patients with Arthritis, as pictured below.

Reprinted with permission from the American Council on Exercise. Based on: Hoffman, DF Arthritis and Exercise Primary Care 20:895-9100, 1993.

The Physician’s Role

Encouraging Physical Activity

Physicians and other health care providers can play a key role in encouraging individuals with arthritis to become more physically active.(ref 4) Eighty percent of Americans view their physician as their primary source of health information. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that physicians advise patients to engage in a program of regular physical activity tailored to their individual health status and lifestyle.(ref 5) The Surgeon General’s Report on Physical Activity and Health notes that “Physicians have a pivotal role in this war against the inactivity epidemic — as educators and motivators. We must continue to stress the importance of physical activity to every patient we see and help to motivate them to choose the road to good health and long life.”(ref 7) This message of the therapeutic importance of physical activity to manage arthritis more effectively is new to many patients with arthritis.

Brief doctor-patient discussions about exercise do translate into behavior change among patients. In a major multi-site trial in primary care settings with diverse patient populations, the PACE (Physician-Based Assessment and Counseling for Exercise) Project found that 3-5 minute counseling sessions increased physical activity among patients. Eighty percent of the physicians reported that their patients were “receptive” or “very receptive” to physical activity counseling and more than 50% of providers perceived that their patients did increase their level of physical activity after this brief intervention.(ref 6) In another randomized trial, patients were asked their response to the statement “If my doctor advised me to exercise, I would follow his/her advice.” Thirty-five percent strongly agreed, 58% agreed while only 7% disagreed and less than 1% strongly disagreed.(ref 4) Listed below are several key points that have been shown to enhance exercise counseling interventions.

Patients with arthritis need clear messages about the benefits of exercise for people with arthritis. It is important to stress that physical activity of the type and amount recommended for health has not been shown to cause or worsen arthritis.(ref 7) While rest is important, especially during flare-ups, lack of physical activity is associated with increased muscle weakness, joint stiffness, reduced range of motion, fatigue and general deconditioning. Hence, current recommendations now emphasize a balance of physical activity and rest. Also, exercise needs to be directed at the entire body, and not just the joints that are affected with arthritis. A simple but highly effective way of helping patients to determine the right balance is by asking them to keep records of their physical activity and arthritis symptoms between office visits. Patterns often become clear within a couple of weeks.

Regular discussions about physical activity at each office visit convey sincerity and interest in the importance of exercise. Among patients, the relationship between physical activity and arthritis is confusing. When joints hurt, a natural response to pain is to reduce physical activity. Also, health care providers often advise patients to rest and avoid exercise during acute flares. Thus, it is easy to understand why some individuals with arthritis mistakenly perceive that all physical activity is undesirable, will only aggravate or worsen their arthritis and should be minimized. It is important to explore with patients their beliefs about exercise, as well as to help them identify barriers and misinformation.

Physical activity counseling is most effective when it is tailored to the individual’s physical and psychological needs. Important considerations in tailoring the advice are: 1) level of readiness to be more active; 2) confidence to begin exercising; 3) expectations about the benefits the person will receive by being more active; 4) previous experience with physical activity; and 5) current lifestyle. Discussions should focus first on encouraging physical activity and allaying fears, as well as helping patients to identify opportunities to become more physically active. Sedentary patients may benefit from receiving simple written directions that reflect a basic exercise prescription to enhance safety, boost confidence and guide them in gradually increasing their levels of physical activity.

Assessing Readiness to Exercise

Psychological readiness to begin exercising is also an important consideration. Theories of behavior change suggest that people vary widely in their readiness to adopt new behaviors. Up to 40% of individuals may be in the “precontemplative stage” where they remain essentially unaware of the problem and have not yet thought about change. For these individuals, realistic goals for exercise counseling are to increase awareness of the importance of physical activity and to personalize information about the benefits that can be anticipated.

For those who express a willingness to be more active, a medical history and physical exam is advised. Specifically, the evaluation should assess the severity and extent of joint involvement, overall level of cardiovascular conditioning and presence of other comorbid conditions.

In the book titled ACSM’s Exercise Management for Persons with Chronic Diseases and Disabilities,(ref 8) The American College of Sports Medicine recommends the following exercise testing program for individuals with arthritis:

- Muscle strength and endurance

- Aerobic endurance

- Joint flexibility and range of motion

- Neuromuscular fitness, including gait analysis and need for orthotics

- Functional capacity to accomplish activities of daily living

Approaches to Physical Activity

- Structured Exercise Programs

- Water Aerobics

- Range of Motion/Flexibility

- Recreational or Lifestyle Exercise

Structured Exercise Programs

The Fitness Arthritis and Seniors Trial (FAST) is the largest clinical trial to evaluate the effects of exercise on osteoarthritis.(ref 9) A total of 439 adults aged 60 and older were randomized to either aerobic exercise, resistance exercise or a control group (health education). Participants in the aerobic exercise group exercised for 40 minutes three times a week; those in the resistance training group completed three 40 minute sessions per week performing two sets of 12 repetitions of nine exercises. The investigators concluded that both types of exercise were associated with similar significant improvements in symptoms of physical disability, improved physical performance and reduced pain.

Water Aerobics

Aquatic aerobic training programs that are offered in therapeutic pools have many advantages related to the warmth and buoyancy of the water.(ref 10) Pools that are designed for persons with arthritis are often kept at much warmer temperatures (e.g., 78-83 degrees) than recreational pools and may have specialized access ramps to make entrance to the pool easier.

Range of Motion/Flexibility Programs

Individuals with arthritis often have a limited range of motion, especially in lower extremity joints. Decreased range of motion associated with knee and hip OA is associated with pain, loss of function, physical limitations and an increased risk of injury and falls. In addition, to receive adequate nutrition, cartilage requires regular compression and decompression to stimulate remodeling and repair.(ref 1) Minor notes that the optimal daily exercise plan to maintain cartilage health should include range of motion exercises. She also recommends that physicians provide specific recommendations; simply advising patients “to stretch every day” is not advisable since affected joints that are lax are easily overstretched and more vulnerable to injury.

Recreational or Lifestyle Exercise

Key Messages from the Surgeon General’s Report on Physical Activity

Physical activity need not be strenuous to achieve health benefits. Older adults can obtain significant health benefits with moderate amounts of physical activity, preferably daily. A moderate amount of activity can be obtained in longer sessions of moderately intense activities (such as walking) or in accumulating shorter sessions of more vigorous activities (such as fast walking or stair walking).

By the early 1990s, epidemiological data were mounting on the dose-response gradient of physical activity and health outcomes. These findings were reinforced by recent investigations that demonstrated that health benefits of physical activity are obtained even with small amounts of moderate-intensity activity. Thus, while improvements in fitness require strenuous and continuous activity on a regular basis, health benefits (i.e., improved serum lipid levels, reduction of blood pressure, weight management, improved cardiovascular risk profile) can be enjoyed by accumulating moderate intensity activity throughout the day.(ref 11)

Additional evidence of the value of moderate intensity exercise comes from recent investigations that have shown that activity need not be undertaken in a single bout to be beneficial. For instance, the benefits from three 10-minute walks or one 30-minute walk are similar.(ref 12 , 13) Studies also suggest that moderate-intensity activity may improve pain, reduce disability, improve fitness and enhance psychological well being.(ref 7, 14, 15) Helping individuals to recognize that “regular exercise” includes a wide range of activities from gardening and using the stairs to more traditional vigorous exercise (i.e., aerobic dance or running) may make physical activity more appealing and achievable to a wider range of people .

In 1996, the Surgeon General released the first report on physical activity and health summarizing an exhaustive review of the research on physical activity. It recommended that people of all ages strive to accumulate 30 minutes of moderate intensity lifestyle activity throughout the day on most days of the week. (for the complete report, http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/sgr/contents.htm).

This new approach to exercise, often termed “lifestyle activity,” can include all leisure, occupational, or household activities that are at least moderate to vigorous in intensity.(ref 16) Examples of moderate-intensity lifestyle activities include walking, raking leaves, and gardening. For persons with arthritis, lifestyle physical activity may be especially appropriate for several reasons. Experts advise sedentary person’s to begin with short durations of moderate intensity physical activity. Short bouts of exercise (as opposed to one continuous session) may reduce pain and prevent injury. Intermittent episodes of activity also allow individuals with arthritis more flexibility in alternating physical activity with rest.

Exercise Adaptations for People with Arthritis

The ACSM has outlined several modifications for exercise for persons with arthritis.(ref 8)

- Begin slowly and progress gradually. The hallmark of a safe exercise program is gradual progression in exercise intensity, complexity of movements, and duration. Often patients with arthritis have lower levels of fitness due to pain, stiffness or biomechanical abnormalities. Too much exercise during a flare may result in increased pain, inflammation and damage to the joint. Thus, beginning with a few minutes of activity, and alternating activity with rest should be the initial goals.

- Avoid rapid or repetitive movements of affected joints. Special emphasis should be placed on joint protection strategies and avoidance of activities that require rapid repetitions of a movement or those that are highly percussive in nature. Because faster walking speeds increase joint stress, walking speed should be matched to biomechanical status. Special attention must be paid to joints that are malaligned or unstable. Control of pronation and shock absorption through shoe selection or use of orthotics may be indicated.

- Adapt physical activity to the needs of the individual. Affected joints may be unstable and restricted in range of motion by pain, stiffness, swelling, bone changes or fibrosis. These joints are at higher risk for injury and care must be taken to ensure that appropriate joint protection measures are in place.

Getting Started

Apparently healthy or non-symptomatic people do not require maximal or diagnostic stress testing for participation in moderate intensity aerobic exercise.(ref 17) Moderate intensity exercise is defined as being well within one’s current capacity, sustainable for 60 minutes, with slow progression. It is performed at 50-70% of age predicted maximum heart rate.

A recent meta-analysis of exercise and osteoarthritis concluded beneficial effects are evident for various types of exercise therapy, but there is insufficient evidence in favor of one type of exercise program.(ref 18) Thus, the most important factor when counseling individuals with arthritis is to help them to select activities they are likely to stay with over time.

Beginning exercisers should be encouraged to identify the type of physical activity they feel most comfortable with, and then begin this activity in short sessions. If patients have had positive experiences with a particular mode of exercise in the past, they are likely to have higher exercise self-efficacy. (Exercise self-efficacy is the belief or confidence people have in their ability to begin and maintain an exercise program and is one of the best predictors of long-term adherence.) For instance, among those who have enjoyed swimming in the past, water aerobics may be an ideal method to increase physical activity. On the other hand, if individuals are not fond of swimming, encouraging them to get into a pool regularly is less likely to be successful than encouraging them to begin a walking program.

For those who enjoy being with others, exercise classes for people with arthritis are a safe and effective way to learn to exercise. Exercise classes are led by qualified instructors and have several advantages. First, exercise technique is emphasized and adaptations based on individual needs are easily arranged. Second, the group offers support and opportunities to socialize. Many of these programs can be found in health clubs, community recreation centers or YMCAs. The Arthritis Foundation maintains listings of a variety of 6-8 week programs offered in your area. Programs include stretching and strengthening (P.A.C.E: People with Arthritis Can Exercise), water aquatics, and others.

If individuals are reluctant to join a class, videos that demonstrate safe exercises to do at home can be rented from local chapters of the Arthritis Foundation. Visit their website at: http://www.arthritis.org/offices/saz/programs/z.asp

Keeping It Going: Exercise Supervision and Training

Some individuals may benefit from a referral to a health care provider with expertise in exercise supervision and training. Physical Therapists and Exercise Scientists with additional training in working with persons with arthritis may play an important role in helping these individuals become more physically active.

Physical therapists (PTs) are optimally trained to develop and evaluate the appropriateness of physical activity programs in persons with arthritis. PTs can carefully assess joint motion, muscle strength and endurance, and performance of activities of daily living. Education about energy conservation, modification of daily tasks, and joint protection is emphasized. PTs can also develop an individualized therapeutic exercise program that individuals can perform at home. Frequently, health insurance programs will reimburse, in part, the services of physical therapists.

Recently, a new type of exercise specialist has emerged to bridge the gap for individuals who have completed a program of physical therapy (or received clearance from their physician) but lack the skills or confidence to continue exercising independently. Clinical Exercise Specialists can play an important role in helping individuals with arthritis become or remain more physically active. While most exercise specialists have the training and skills to work with apparently healthy individuals, Clinical Exercise Specialists have additional training and experience that enable them to work with persons with arthritis and other chronic medical conditions. This advanced training is broad in nature and includes an emphasis on exercise physiology, motivation, goal setting, biomechanics, exercise technique and the needs of individuals with chronic medical conditions. While health insurance programs generally do not reimburse the costs of the Clinical Exercise Specialist, often their fees are set at a lower level to encourage ongoing use of the trainer’s services.

Clinical Exercise Specialists can often be found in hospital-based wellness settings. Many provide services to clients in their own homes to make exercise more convenient and less burdensome. Currently, several organizations certify exercise scientists who have undertaken additional training and experience working with individuals who have chronic medical conditions. Two of the best are the American College of Sports Medicine (Clinical Track Certifications) and the American Council on Exercise (Clinical Exercise Specialist). Both organizations maintain lists of individuals who are currently certified in your area.

Selected References

- Andersen RE, Blair SN, Cheskin LJ, Bartlett SJ. Encouraging patients to become more physically active: The physician’s role. Ann Int Med 127(5):395-400, 1997.

- Minor MA. Exercise in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 25(2):397-415, 1999.

- Ytterberg SR, Mahowald ML, Krug HE. Exercise for arthritis. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol 8:161-189, 1994.

- Lewis BS & Lynch WD. The effect of physician advice on exercise behavior. Preventive Medicine 22(1):110-121, 1993.

- 5. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Clinical Guide to Preventive Services. 2nd edition. Alexandria, VA. International Medical Publishing, 1996.

- Long BJ, Calfas KJ, Wooten W, Sallis JF, Patrick K, Goldstein M, et al. A multisite field test of the acceptability of physical activity counseling in primary care: project PACE. Am J Prev Med 12(2):73-81, 1996.

- 7. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity and Health: A Report ofthe Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 1996.

- 8. American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Exercise Management for Persons with Chronic Diseases and Disabilities. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1997.

- Ettinger WHJ, Burns R, Messier SP, Applegate W, Rejeski WJ, Morgan T et al. A randomized trial comparing aerobic exercise and resistance exercise with a health education program in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. The Fitness Arthritis and Seniors Trial (FAST). JAMA 277(1):25-31, 1997.

- 10. Minor MA, Hewett JE, Webel RR, Anderson SK, Kay DR. Efficacy of physical conditioning exercise in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 32(11):1396-1405, 1989.

- Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN. Physical activity and public health: A recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. JAMA 272:402-407, 1995.

- 12. DeBusk RF, Stenstrand U, Sheehan M, Haskell WL. Training effects of long versus short bouts of exercise in healthy subjects. Am J Cardiol 65:1010-1013, 1990.

- 13. Jakicic JM, Wing RR, Butler BA, Robertson RJ. Prescribing exercise in multiple short bouts versus one continuous bout: effects on adherence, cardiorespiratory fitness, and weight loss in overweight women. Int J Obes 19:893-901, 1995.

- 14. van Baar ME, Dekker J, Oostendorp RA, Bijl D, Voorn TB, Lemmens JA et al. The effectiveness of exercise therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: a randomized clinical trial. J Rheumatol 25(12):2432-2439, 1998.

- Bautch JC, Malone DG, Vailas AC. Effects of exercise on knee joints with osteoarthritis: A pilot study of biologic markers. Arthritis Care Res 10:48-55, 1997.

- strong>Dunn AL, Andersen RE, Jakicic JM. Lifestyle physical activity interventions. History, short-term and long-term effects, and recommendations. Am J Prev Med 15(4):398-412, 1998.

- Gordon NF, Kohl HW, Scott CB et al. Reassessment of the guidelines for exercise testing. Sports Med 13:293-302, 1992.

- van Baar ME, Assendelft WJ, Dekker J, Oostendorp RA, Bijlsma JW. Effectiveness of exercise therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. Arthritis Rheum 42(7):1361-1369, 1999.

Suggested Resources

- American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 5th ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1995.

- Nieman DC. Arthritis. Cotton DJ, Andersen RE (eds): Clinical Exercise Specialist Manual. San Diego, CA, American Council on Exercise, pgs 213-224, 1999.

- American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Exercise Management for Persons with Chronic Diseases and Disabilities. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1997.

- Arthritis Foundation Website